BUT, TODAY ADS COLLECT US

Mass-production advertising is establishing our whole pattern of life – principles, morals, aims, aspirations, and standard of living. We must somehow get the measure of this intervention if we are to match its powerful and exciting impulses with our own.

But Today We Collect Ads – Allison and Peter Smithson, 1956

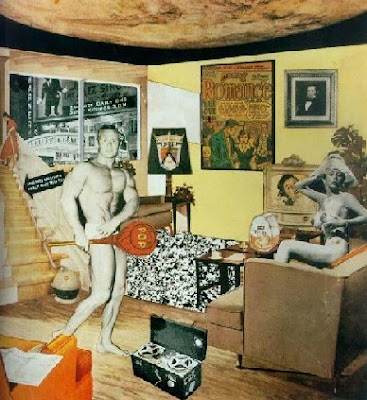

Richard Hamilton, Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, 1956

The Smithsons and Richard Hamilton collected ads. They went to their magazine stands, took their scissors, and began to collage carefully produced images meant for mass consumption. The Smithsons used them to learn about domestic desires while Hamilton collaged those desires into perspectival space.

The advertising business just does not have it that easy anymore. As TV viewership and magazine circulation numbers dwindle the advertising world needs new ways to reach eyes and ears. One way is by creating advertising that does not look like advertising, such as the ad for Reebok featuring Heidi Northcott and Chuck Lidell working out nude. The advertiser, Reebok in this case, puts out media that looks home-made and amateur but that, because of its uniqueness, many media outlets and regular people may want to, inadvertently, distribute on their own. They trust that the force of the network will be powerful and in that way cut through the clutter of visual information each of us face daily. The mass as media.

Heidi Northcott and Chuck Liddell nude workout – part of a viral marketing campaign by Reebok

In this way the advertiser seeks to embed itself in the general culture, turning us into mini-conduits of their message. They count that we will use email, facebook and twitter profiles, blogs, etc… to tell our friends. However, our inadvertent labor for the advertiser does not end there. Once we post it to one of the many social-media outlets we are continuing our free labor for those that seek to sell us something. Our information is collected and used to send us increasingly more tailored commercial information. Daily life as commodified data.

As even our social interactions become part of larger obfuscated economic systems, one question arises: can we do anything about it? It seems that the first task is to find tools to visualize the invisible yet pervasive control systems. Then, we hack them. But, today ads collect us.

DATA LANDSCAPES AND THE VIRTUAL GIZMO

The quintessential gadgetry of the pioneering frontiersman had to be carried across trackless country, set down in a wild place, and left to transform that hostile environment without skilled attention. Its function was to bring instant human comfort into a situation which had previously been an undifferentiated mess…

The Great Gizmo – Reyner Banham, 1965

Were it not for a macbook pro, a verizon wireless router, and many many servers hidden in generic buildings all over the world I would not be writing this, proving that the physical gizmo still matters. But equally as important to this text is the virtual infrastructure that blogger.com has created, allowing me to easily share information. In this way blogger.com acts as a gizmo that helps me, without technical skill in website coding, to begin to colonize an otherwise hostile data landscape. If we think of a gizmo, as Banham does, as a tool that brings human comfort undifferentiated messes, could blogger.com be thought of as a virtual gizmo?

After all, the word gadget, often synonymous to gizmo, has already been appropriated as the data visualization mini-applications usually found in a PC’s tool bar. Virtual gizmos could be more instrumental (tool-like) and critical, defined as digital instruments we can use to uncover and organize otherwise obfuscated and hidden information in the data landscape (not just digital thermometers and clocks).

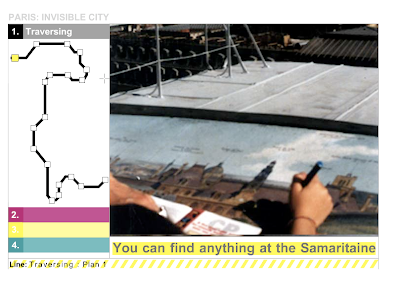

By this definition virtual gizmos would include everything from social media platforms (revealing your friendships, tastes, and ideas) to more conceptual projects such as They Rule, a web platform that allows the user to visualize the relationships among the most powerful institutions in the United States. Another example is Bruno Latour’s Paris: Invisible City. In the site Latour seeks to discover hidden relationships and itineraries in the physical city by mapping ordinary, forgotten objects.

Image from Bruno Latour’s Paris: Invisible City.

This way of thinking is nothing new to architects, who traditionally develop a variety of intellectual tools to organize vast amounts of abstract information. The type of information we care about, however, has changed. In the essay Spatial Practices in the Margin of Opportunity architect Markus Miessen discusses the political social changes affecting practice today and concludes that:

Apart from simply opposing to a purely formal approach, they object to the idea that there are such terms as high and low culture. The social ambition of these practices is rooted in a much more heterogeneous understanding of society and consequently the city. The protagonists of such socio-political urban practice take popular and marginal cultures into account. They base their work on an urban sociology, which fits with the organization and experience of its citizen and propagates a much more direct relationship with the city. (Did Someone Say Participate, Page 286)

In other words, the new spatial practice is expanding its role to, like Latour, begin to uncover the hidden networks that compose a city, a region, a nation. The virtual gizmo used as a mapping tool becoming instrumental to uncover and understand networks and systems at many scales.

HACKING OUR WAY IN

We now face large neo-liberal systems and networks of commodification that are hard to see and, without accurate visualization tools, impossible to change. In that context hacking, or the re-configuration of systems to work in ways other than what they were intended to, has become the favorite tool of activists against the commodification of our digital and physical spaces.

The idea, however, could also extend to the larger political, social and economic systems that the virtual and physical gizmos are trying to organize. It is no longer enough to simply uncover relationships. Various practices, as different as Estudio Teddy Cruz and Toshiko Mori’s nascent Vision Arc, are beginning to use the power of the virtual gizmo, or relational mapping tools, to find ways to hack systems at all scales. As Miessen puts it, “Today’s spatial practice not only uses experimental research related to transient conditions of urban society, but also applies physical and non-physical structures in order to change and alter specific settings.” (Page 288)

In this case the virtual gizmo reveals moments of opportunity for a designer while the physical gizmo can be deployed as a way to address the situation. As for those spatial physical gizmos they should, perhaps, look at their cousins in tactical gyzmology, described by the Tactical Media Crew as: “…what happens when cheap ‘do it yourself’ media made possible by the revolution in consumer electronics, are exploited by those who are outside of the normal hierarchies of power and knowledge.”

OTHER REFERENCES

Tactical Media

Reassembling the social: an introduction to actor-network-theory

#lgnlgn

#remixrevisitremaster

#gizmosandads

Leave a Reply